Esprit d'Accord

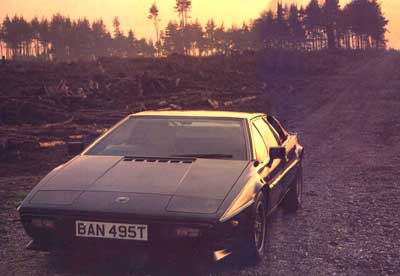

This series-2 Lotus

Esprit is OK by Roger Bell.

It has superb road manners, a fine shape and a strong pedigree.

For a mid-engine supercar by a grand prix car builder, it's a bargain

Supercar Classics, June 1990

by Roger Bell

photography by Mervyn Franklyn

It's a familiar story. The good news about old Lotus Esprits is that they're cheap to buy. The bad is that rock-bottom ones, costing as little as £3,000, will be dogs in need of expensive attention – quite possibly a new chassis if you can get one – beyond the reach of the impecunious. 'Esprits of the late '70s were of terrible quality,' says Miles Wilkins, oracle of Fibreglass Services in West Sussex, Lotus specialists of world renown. 'Lotus had no money. Chassis got one coat of black paint to protect them. Now they're rotting away.'

Poor reliability and durability are deep-rooted problems that have dogged Lotus since its birth. The only good to come from the sorry saga is that prices of cars from the post-Elite/Elan/Europa era have not spiralled out of sight like those of most contemporaries in the junior supercar league. 'Poor quality has frightened people away, dragged prices down,' says Wilkins. 'Chapman was so busy redesigning the DeLorean he ignored his own cars. It's a tragedy.'

Anyone who puts money into a used Esprit is taking a brave gamble, but it's one that can pay off if you buy well. After all, Ferrari's 308, now costing perhaps 10 times as much as an Esprit of comparable age and condition, is barely twice as good dynamically, and arguably inferior aesthetically, to the Giugiaro-styled Lotus.

Colin Fitch does not regret buying an Esprit eight years ago, but then he bought very well indeed. Early in the '80s, he'd given up on a second-generation Elite, which fell apart in the usual self-destruct way.

Fitch put his money, £8,750 of it, into a four-year-old, 14,000 mile, two-owner S2 – one of the 100 black-and-gold JPS cars that commemorated Mario Andretti's formula one world championship win in the like liveried Lotus 79. Fitch reckons that Esprits in general are still depreciating in real terms. If you can afford a new Ford Fiesta, you have more than enough for a good Esprit. Perhaps not Fitch's car, a pristine example of a rare limited edition, valued at an exceptional £12,000, but certainly one that will swivel eyes, puff egos and tease senses, never mind excite.

The early '70s saw Lotus, under engineering director Tony Rudd, working on two new projects. One was code-named on two new projects. One was code-named M50, which became the Elite (today's Excel by evolution), the other M70, later the Esprit, mid-engined successor to the Europa which itself ended its run on a much higher plane than when it had started with Renault power.

The shape of things to come was revealed at the '72 Turin Show where Giorgetto Giugiaro, in collaboration with Colin Chapman, displayed a wide, wedge-nosed styling exercise based on an extended Twincam Europa chassis. Alongside, on the Ital Design stand, was its inspiration, Giugiaro's dramatic Maserati Bora-based Boomerang.

The Esprit was appreciably bigger than the Europa. The wheel base went up from 91 to 96 inches, the track from 53.5 to 60 inches. Instead of the Ford-based twincam used in the Europa and Elan, which had reached its development potential, the Esprit was powered by a new 2.0 litre all-aluminium, 16-valve twincam (the 907), based during its development on the block of a Vauxhall engine that mirrored Lotus's thoughts on a 45-degree slant-four that could be doubled up into a V8.

The V8 never went into production (experimental prototypes were apparently disappointing) but the canted all-Lotus four did, in '72, first for the new Jensen-Healey, later for the Elite. Three years (and an oil crisis) later, the penny-pinched Esprit, looking much like Giugiaro's show stopper, was announced, though sales were delayed until the following year.

Performance of those early cars was disappointing, even though Lotus kept the weight down and boosted power of the Dellorto-fed 907 engine to 160bhp. Torque was rated at 140lb ft. A crucial element of the M70 project was the use of a Citroën SM gearbox/final drive (also used in the Maserati Merak). Lotus continued to use this transmission until the recent reskin, when it was superseded by a stronger Renault Alpine unit.

Like the Elan and Europa before it, and the M50 Elite, too, the Esprit was based on a stiff backbone chassis carried by all independent suspension. The double-wishbone layout at the front was basically Opel Rekord (later Triumph Herald and Toyota) but the rear-end was pure Lotus, fixed length driveshafts acting as upper transverse links to wide-based box-section semi-trailing arms beneath. Not until the S3 was introduced in '81 were the driveshafts freed of their suspension-locating duties.

The original Esprit, produced 1976-78, got a good press for its grip, a reserved one for lifeless handling. Performance was rated as indifferent (125mph was barely good enough as this level), quality poor. Lotus did its reputation in the US irreparable harm with these early, ill-sorted cars. Despite its long gestation period, hampered by Lotus's perennial financial difficulties, the Esprit needed more development time.

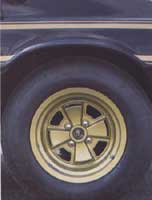

Lotus made about 1500 Esprits in the first 30 months of production before introducing the S2, which embraced a number of minor improvements designed to silence the critics. Handling was crispened (harder dampers, wider track, ball-raced steering), performance increased (E-camshaft standardised), quality scrutinised (to not much avail). The front spoiler became an integral part of the body, Speedline wheels replaced the original Wolfraces, new air scoops fed the engine, and the tail sported Rover SD1 lamp clusters. Switchgear, instruments, seats and badging were changed, too. And that's the car we have here.

The condition of Colin Fitch's eye-catching S2 (number 20 in the JPS run, according to the dash plaque) certainly casts doubt on the quality problem. True, the car is not in everyday use and its mileage is very low, but what you see in Mervyn Franklyn's photographs is not an expensive restoration but almost exactly what left Hethel at the back end of '78. The body, paint, interior and most of the running gear are all original.

Colin Fitch has done so little to this car he can memorise the work of eight years. Alarming fidget bordering on instability betrayed worn front suspension bushes at 20,000 miles, necessitating new wishbones (modified Opel Rekord). 'That's typical,' says Wilkins. Other replacements have included a fresh set of Monroe dampers, two springs, engine camshaft belts and a universal joint, all fitted by Cambridge based Peter Day (now closed), enthusiastically commended by owner Fitch.

Cosmetic attention has included refurbishing the wheels, removing non-standard stripes from the bonnet, replacing the original steering wheel (which a previous owner had swapped for a larger one, presumably in the quest for instrument visibility) and reviving a couple of badges. Fitch points to some minor gel cracks and stress marks (which I can barely see) in the glassfibre, but the body and paintwork, gold embellishment included, are first class.

Despite the Esprit's notorious reputation, Fitch is reasonably happy with the build quality of his car. 'I've had no serious mechanical or electrical troubles. Generally, it's stupid little things that go wrong.' He cites the recalcitrant rev counter as an example. 'Spares are not crazy money or difficult to get,' he adds, though Miles Wilkins, who has trouble (like other franchised dealers) getting hold of many Lotus sourced parts, does not wholeheartedly agree. His new Lotpart enterprise lists in a quarterly bulletin those tricky spares that are now sourced elsewhere.

Like Wilkins, Fitch castigates Lotus for amalgamating its spares division with that of Vauxhall's, just off the M1 near Dunstable. 'They don't care,' says Wilkins. 'It's carnage in a crate when the bits arrive.'

Clambering into Fitch's car at once reminded me of the Esprit's greatest short comings; it is impractically wide, and tricky to reverse. Forward visibility through the huge, acutely raked screen (not quite the flat sheet of glass it seems) over the arrow-shaped nose is superb, but that to the rear is awful. You sit low and laid back in a reclining fixed-back bucket seat that hugs your hips but leaves your shoulders free to loll. Pedals are offset to the left, so you sit slightly askew behind a fixed, thick-rimmed steering wheel that masks the top quarters of the small instruments, housed in a banana-shaped binnacle. I recall this strange appendage suffering from vibroquivver in some Esprits, but that of Fitch's car was rock steady.

There are plenty of other distracting irritations, among them reflections in the minuscule Smiths dials, humdrum BL/Triumph switchgear and fittings, an elbow-bashing central divide (camouflaging the car's backbone chassis), and poor cockpit ventilation. The cabin can get stuffily hot, and the windows murkily misty, without an open (powered) window or air conditioning, which Fitch's car does not have. I can also get crowded. Despite the width of the low slung cockpit, there's barely room for a map, never mind a handbag, when both seats are occupied. As the front boot is full of spare wheel, all luggage must be deposited in the warm-box beneath the heavy rear hatch, shared with the engine and battery. No, the Esprit is not a practical car.

The unblown 2.0-litre engine (bombproof according to Wilkins, provided it's properly maintained), starts readily from cold with a coarse bark. Only hot is it reluctant to fire, and then only after much black-smoke stutter that's minimised by flooring the throttle before turning the key.

The engine revs smoothly and eagerly, up to 7000rpm if you've a mind, but it has none of the aural appeal of a Latin V6, never mind the Ferrari V8, even allowing for mid-range raspiness. Normally, pleasing exhaust buzz is drowned out by tiresome down-bowel boom that assails disagreeably. In its S2 test in '79, Motor asserted that the din (81dB) registered in the cockpit at a steady 70mph was high enough, according to the Noise Abatement Society, 'to cause a harmful mental or physical effect on the driver.' I don't thin Fitch's car is that bad, but refined it is not.

Performance is stronger than expected. What's more, delivery is broadly spread so the engine will slog it out flexibly at low revs almost as keenly as it will scream, quite viciously from 4000rpm, to the cut-out. There's no red line on the tacho. The later 2.2 was torquier at mid-range revs – and quicker through the gears, as well – but the 160bhp 2.0-litre S2, tipping the scales at around the ton, was no slouch, even though acceleration (0-100mph in 23 seconds) was inferior to the Elan Sprint's (20 seconds) and pales against that of the latest 264bhp Esprit Turbo SE (a stunning 12 seconds).

Top speed of the S2 is a disappointing 125-128mph, despite unusually clean penetration for a car drawn in the early '70s. Lotus might have made more of a 0.34 drag factor when the norm was much worse. The rate at which the needle sank on Fitch's petrol gauge served as a reminder that the Esprit is neither frugal nor a long-distance runner, 14.5 gallons (housed in two tanks) giving a range of little more than 250 miles.

A slightly sticky, lots-or-nothing throttle action (not typical, asserts Wilkins) detracted from cog-swapping fun more then the sharp clutch or clonky gearchange, short in throw but heavily spring-loaded in the three-four plane. Swift, decisive movements are needed to shift cleanly (strength too, to find reverse), the long linkage aft introducing a degree of imprecision not found in the front-engined Citroën SM, source of this Lotus's five-speed gearbox.

The Esprit's magic lies not so much in its drivetrain, which does the job without distinction, but in its chassis. Even by today's standards, the handling and roadholding are brilliant. As only 40 percent of the car's weight is carried by the front wheels (the heavily laden rear ones explain fantastic off-the-line traction and slingshot 0-30mph times) there's no power-assistance for the steering. That's not to say the S2 wouldn't benefit from hydraulic help for parking or manoeuvring, when steering is stodgily heavy.

Properly on the move, the helm not only lightens but livens up. The small, thick-rimmed wheel gently writhes and kicks, accurately communicating surface topography. The dead helm criticised in early road tests was not evident in Fitch's car, which squats on the road like a wide-tracked racer. More to the point, it corners like one, all-square, settled, responsive, ultra-stable. You flick it through bends with wristy movements, aiming the nose rather than steering it.

On the track (owner Fitch does the odd club sprint) it's apparently the back that relinquishes grip first. In the public domain, nothing lets go, or seems likely to do so. Even when hurrying in the wet, the grip is stronger than the nerve of most circumspect drivers. Nor are the lightly laden front wheel prone to premature lockup when the all-disc brakes (inboard at the back) are used in anger.

Despite its tenacity, the Esprit is not especially agile. Nearly 10 inches wider than a 911, it's too broad in the beam to make the most of its cornering grip on country lanes where a sibling Seven would outrun it. Super-smooth roads are not an essential ingredient for Esprit de corps, though. The firm, no-roll ride is well on the right side of harsh or crashy. Nor does the structure shake or rattle. Fitch's car feels as solid as the day it was made, though there are trim squeaks from the black-and-tan decor – plusher than I remember despite all the shiny black plastic, which looks better than some of the fittings sound or feel: doors shut with a dull clatter, switchgear is sloppy.

Allowing for these and other faults, Fitch's S2 Esprit seemed to transcend Lotus's innate quality problems. It made the genre seem underrated, never mind undervalued. After driving this outstanding JPS, hardly a typical 12-year-old Esprit, I found myself scanning the classifieds for post-'81 S3s which have the same 160bhp as the S2 but, like the interim 2.2-litre S2.2 (of which only 42 were made), appreciably more torque (160lb ft instead of 140). They also have a galvanised chassis, which Wilkins confirms arrests the rot, and revised suspension, as well as various cosmetic improvements. Unfortunately, they also have Triumph Herald-based front suspension, as on the Elan/Europa/Elite/Eclat, which for reasons of rationalisation, displaced the superior Opel Rekord-based set-up.

Not until 1985 was this inferior Triumph front-end displaced by respectable Toyota running gear, which included ventilated discs in place of solid ones – not that the brakes of earlier Esprits were lacking in performance. The best pre-reskin non-Turbos, then, will carry B-reg plates, or something later. Other models to look out for? Wilkins suggests the original '76 S1 orange gel-coated car, and the rare S2.2, once the least-wanted of all Esprits.

The successful limited-edition JPS cars were introduced at the NEC show in '78, shortly after the S2 had been announced. Later, in 1980, a second limited-edition run of Esprits was to launch the Turbo, initially in the blue, red and silver colours of Essex Petroleum. But that's another story.

|

|