The HOLY TRINITY

Mid-engined masterpieces needn't cost top money.

There's nothing like a mid-mounted engine to make a car feel very special. Mid-engined cars sound different. When the power source is behind you, but ahead of the rear wheels, a car's main masses can be centred low and well inside the wheelbase, racing car style, for best handling and body control. You can feel the chassis hug the road from the moment you begin to drive. The unusual source of engine noise — through a bulkhead a few inches behind your shoulders — can only add to its exotic nature.

Once, enthusiasts of ordinary means were denied mid-engined cars, all bar good but small-engined creations like the Fiat X1/9 and Lancia Montecarlo. But things are changing. Here we have assembled a collection of three fine cars — Lotus Turbo Esprit, De Tomaso Pantera and Ferrari 308 GTB — all priced between £15,000 and £25,000 for the best examples, which may not make them bargains, but definitely brings them out of Millionaire's Row. For the patient, good examples can be found for under £20k. All three hit the car lover's high notes: they're genuine high performance cars, they have fascinating and important heritages, they're great to drive and (for those prepared to search) they're available.

As far as usability goes, each strikes the balance most of us seek. None of the three is so rare and exotic that it can't cope with some day-to-day running or take its owner on holiday through France, say. Yet each is rare and specialized enough to be a real eye-grabber and to need intelligent and sensitive ownership. These are cars, in short, for discerning classic car enthusiasts.

Each of this trio is well enough known to have a reputation that precedes it. People will tell you that Panteras are fast, brutish and unreliable; that Lotus Esprits handle beautifully and are unusually good value but none too well built, and that Ferrari 308 GTBs are lovely, but cramped and fragile. But reputations frequently contain as much myth as fact, which is why we've brought together our tiro here. Beyond their broad mechanical description 'mid-engined two-seaters' these cars are really quite desperate. Their layouts accurately reflect the preferences of the strong-willed characters (Colin Chapman, Enzo Ferrari and Alessandro De Tomaso) whose restless energy bought them to life.

The youngest car here, by nearly two decades, is the 1991 Lotus Esprit SE. We're included it to acknowledge its status as a modern classic, and to test the other two contenders against a car of unashamedly modern manufacture. In fact, the Esprit's roots go back almost as far as the De Tomaso Pantera and Ferrari 308 GTB. Based originally on an emotive and much-admired Giugiaro show car of the early 70's, the production Esprit appeared in 1976 to cater for the sort of Lotus owners who wanted to move on from their Europa Twin Cams.

The layout of the earliest cars is little changed from the Esprits made now: backbone chassis fabricated from sheet steel (galvanised from the early 80's); longitudinal-mounted Lotus twin-cam, 16-valve, in-line four-cylinder engine with alloy block and head; five-speed transaxle from a Renault Alpine (replacing the Citroen five-speeder previously used); all-independent coil-sprung suspension by double wishbones (front) and trailing arms with upper and lower links (rear); unassisted rack and pinion steering; powered disc brakes all round, and differently-sized wheels and tyres front and rear. The Turbo made its appearance in 1981, and turned the Esprit into a true supercar. The Giugiaro shape was redesigned in 1987 by Peter Stevens, then Lotus' chief designer, and various chassis stiffening and engine mounting mods were made. The work added 200lbs, but the new car was much improved aerodynamically. Then the hugely powerful and quick Esprit SE burst upon the scene in 1989.

The key to all Esprits, as with the rest of Colin Chapman's remarkable cars, is that they extract out-of-the-ordinary performance from a collection of relatively ordinary components. The Esprit SE, as here, takes this to extremes. The engine appeared first as a 2-litre in the Jensen Healey in 1972, but in this turbocharged guise it extracts 264bhp at 6500rpm (and 261lb ft at 3900rpm) from only 2.2 litres. According to Autocar, a healthy SE could achieve 159mph flat out, erupt from 0-60mph in 4.7 secs and 0-100mph in 12.5 — but still deliver 22 to 24mpg in brisk use.

The Ferrari 308 GTB had its roots in the Dino 246 GT and particularly in the softer, roomier 308 GT4, dubbed Dino V8 at the time, which came along in 1973 to replace the 246, bringing with it a brand new 3-litre V8 engine. Though the two-seater GTB's transverse mid-engine and compact dimensions (it was three inches lower than the GT4, and three inches shorter) were fairly far from the traditions established by Ferrari's succession of V12 road cars, the biggest break with marque tradition was its use of a glassfibre body — a big departure for Ferrari's traditional body builder, Scaglietti.

Glassfibre GTBs were launched in 1975 and survived only two years in production. The market's feeling that real Ferraris needed to be shaped in metal killed it, along with Scagliett's difficulty in building the plastic bodies down to a price. Only about 120-odd right-hand-drive versions are thought to survive. Yet the glass' 308 GTB is now much admired for the enduring excellence of its body finish, its lightness (aficionados say it is around 200lb lighter than the all-metal cars that came later) and, of course, for its inability to corrode. All other Ferraris of the era were ravaged by tinworm. They were fast, though. The 0-60mph sprint was claimed to occupy 6.5 secs, the car passed 100mph in 17.5 and on a good day the top speed was 150mph. Most owners today say 135-140 is closer to the truth, though the acceleration rally is notably brisk for a car with only 3-litres, normally aspirated.

Mechanically, the 308 GTB adheres to Ferrari values: tough tubular chassis of elliptical-section tube, zesty and high-revving engine of surprising robustness with similarly strong gearbox. Suspension is by double wishbones front and rear, the brakes are all-disc and the rack and pinion steering (less direct than some at 3.3 turns lock to lock, considering the poor turning circle) is unassisted.

Ferraris of the era are often now criticised for problems with details — trim, instruments, electrics — but I owned one of these for three years and 15,000 miles in the mid 80's, and never even had a light bulb blow.

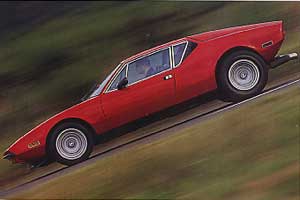

As the first exotic car I ever drove, back in 1973, the De Tomaso Pantera is also close to my heart. The car we test here is of identical age, but has been restored and debugged so that it works far better than most Panteras do. The car evolved from the Mangusta, a flawed but beautiful creation with a flexible backbone chassis and ill-considered suspension but a body penned by Giugiaro, when he worked at the design house Ghia.

The Pantera, the Mangusta's better-founded replacement, was designed by Tom Tjaarda, then a new boy at Ghia. Alessandro De Tomaso — a successful Argentinian racing driver who settled in Italy after falling out with the dictator Juan Peron, and began building small-volume racing and sports cars after the OSCA machinery he once drove — had just acquired Ghia as part of a quest to produce cars aimed at attacking existing sports car markets.

Two targets in particular stood out. De Tomaso dreamed of threatening Ferrari with a full-house supercar that really looked the part (hence this desire to have his own prestigious coachbuilding firm, ready equipped with expertise and heritage). But he yearned even more to involve a big-scale car company in producing one of his designs.

In the early 70's, two great but entirely dissimilar minds began to think alike. De Tomaso hatched the Pantera to spearhead his plans. Henry Ford II, grandson of Henry, had lately failed to acquire Ferrari and was on the lookout for an Italian alternative that would prove that Americans had good taste, while negating the Chevy Corvette in US showrooms. It had undoubtedly tickled his fancy that De Tomaso's previous Mangusta (Italian for 'mongoose', an animal which hunts and kills Cobras) had used a Ford V8 engine.

Wily De Tomaso gave the Pantera a unitary steel chassis to make it more appealing for big-scale manufacturers. The suspension was by double wishbones, coil springs and anti-roll bars front and rear, and plonked right in the middle of the whole structure was a 351cu in (5.7-litre) Ford 'Cleveland' V8 engine, rate initially at 300bhp. It was mated to an impressive-looking ZF transaxle whose huge length and genera size, together with the bulk of the 351, conspired to give the car a hefty rearward weight bias and to intrude rather alarmingly into the space allowed for occupants. Still, the early Pantera, as seen here, had a clan dart-like profile and made many other supercars of the time seem bulky and fussy.

Henry Ford's tenure of the De Tomaso companies, and his flirtation with the Pantera lasted only a couple of years. The cars were poorly made and, post-Ralph Nader, US buyers had no qualms about complaining loud and long about their shortcomings. Suspension wore prematurely, electrics and trim caused hideous problems, the compromised driving position was nothing like your Thunderbird-driving Yank ever expected, and the car's huge performance — 0-60mph in 5.2 secs, 0-100 in 14.5 — got together with its tail-happy handling to produce a car which scared the unwary.

Henry II fell out of love with the whole idea, and De Tomaso took back control of his companies, all except for Ghia, which survives today in the Ford stable. In all, around 10,000 Panteras were built between 1971 and 1993, when production finally came to an end after the production of numerous wide-arched GTs, GTSs and GT5s. None of the later breed were nearly as beautiful as Dominic Wood's gorgeous, unwinged 1974 original.

So that's it then, right? In this company, the Pantera's discredited. In my book, not a bit of it. When I drove this car I was really surprised by the gap between reputation and actuality. Certainly the Pantera has a driving position that's far from ideal. The wheel is low and fairly far away, nestling between your knees which must be necessarily high because the pedals are too close. This is a classic 'gorilla' driving position. At your right elbow (in this left-hand-drive car) is a huge bulge in the engine bulkhead, just to fit in those vast all-iron mehanicals. It smacks of crudity. And yet, when you begin to drive, it's really pleasant. The clutch is heavy but has a shortness of travel and a strength of bite which is downright enjoyable. The brakes respond powerfully, and there's a very firm — even Ford-like — pedal. The throttle is quite light and has a long travel, but you don't need much to get action. This is your classic piece of understressed Detroit iron. It can fairly launch you off the mark even if you only ever change up at 3500. You can rev it to 6000, says the tacho, but you'd be crazy — first, because there's no need because grunt comes pouring through in the next gear if you change at 4500rpm, and second, because the gorgeous rumble of the V8 (this car, imported from the US in 1990, has a nonstandard exhaust system with four mighty tailpipes) sounds best at lower revs. You can sense the oversteering tendency the moment you corner with any effort, but as with many Panteras, Dominic's car uses massive rear tyres to bring it to heel. You can feel the rearward mass in the ride, but in brisk driving the Pantera stays obediently in line, and its light steering seemed precise. No doubt that this is a point-then-squirt car, but one that's solid, capable, fast and fun to drive.

The Ferrari is very different. The pride and joy of a BBC engineer, Roy Barugh, it is a far lighter, sweeter-revving car but seemingly shorn of about half the Pantera's easy torque. Then engine is lovely, vocal and strong when you rev it (I've always been afraid of the early 308's 7700rpm redline) yet amazingly flexible down around 3000 in top. The clutch and brakes require quite a push, but the heaviest control is the rifle-bolt gated gearchange, which was satisfying to use well, but made the Pantera's ZR 'change (also elegantly gated) seem smoother and more rhythmical.

Ferrari 308s handle well, with a bias towards understeer on turn-in. Oversteer is never what you seek in mid-engined cars (unless it's a Lancia Stratos and your name is Sandro Munari) and I never managed to induce it in the car I owned. Nevertheless, the 308 will move obediently closer to neutral if you throttle-off in the middle of a hard corner. It has almost zero body roll, yet despite a distinct lack of suspension travel it is well damped and rides flat. Its happiest feature is the lovely, snug driving position and the way the ultra-low roofline seems to mould itself around you, almost like a garment. Some testers find a 308's minimalist interior a feature worth criticising, but I always enjoyed its simplicity and absence of pretension. The trim parts used aren't impressively finished by today's standard, but you can say that for nearly all cars of the class and time.

Which brings us to the Lotus, so much more modern than the others. If the Ferrari is snug, the Esprit is snugger, and in a different way. It's not so airy and feels bigger than the others, with a deep, supportive tub for the driver, a low roof (too low for tall drivers) and high side window sills. The wide, winged instrument binnacle sits ahead of you, almost at eye-level, so that you sight just over it to apexes.

Dynamically the Esprit is the best of the three, by quite a margin thanks to its extra 20 years of development and tyre technology. It has awesome grip in corners, and refuses to display significant understeer, let alone threaten to poke its tail. You can provoke it playfully in dead slow corners with power, but the car's every response makes it clear that this machine is intended to be driven modern race-car style, with everything nicely in line. The Renault-derived gearchange is notchy and not so well defined as the others, but the softness of it's longer-travel clutch makes the gearchange process more easily and more forgiving than theirs.

This is the only car with turbo lag, so it can seem a little unresponsive when you begin to drive. But get it percolating about 3000-3500rpm and it fairly hurls you down the road. It is the fastest of the three; decisively quicker than the Ferrari, ultimately faster than the Pantera, whose instant torque often makes it seem the energetic car of the three.

It is damnably difficult, reaching a favourite from a group like this because each is a fine car to drive. For many people, perhaps the majority, owning a Ferrari is the pinnacle, and the others are half-measures. For people like that, the 308 GTB will not disappoint, because what goes with the hallowed badge is an excellent, agile, responsive car. For the lover of Detroit muscle, and of the effortless progress it brings, the Pantera makes eminent sense. It is a compelling car, and the thorough development and resulting capability of our test example validates the original concept.

Me? I've had the Ferrari experience already, so I'd want the one I could drive most often. It's the Lotus; the one in this selection which would best stand up to plenty of use.

|

|