Lotus

Esprit S4 v Porsche 911 v Honda NS v Ferrari 348tb

Autocar Magazine

July 1993, Stephen Sutcliffe

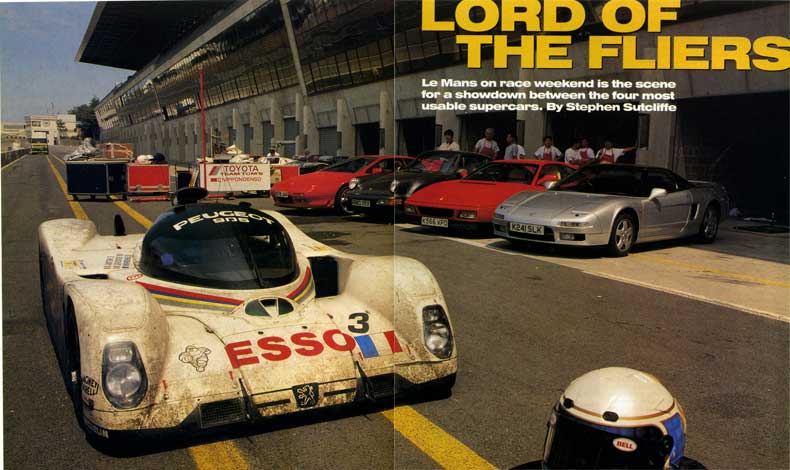

Le Mans on race weekend is the scene for a showdown between the four most useable supercars.

Beaming into the 911's rear-view mirror, I had to pinch myself. Emerging from the belly of one of Sealink's finest was a dazzling silver Honda NSX, its chin kissing the tarmac almost by way of a greeting as it crept down the exit ramp. Then came a bright red Lotus Esprit S4, followed noisily by the prima ballerina of our extravagant convoy, a beautiful Ferrari 348tb – piercing rosso red, naturally.

Thinking back now, we must have been mad not to point those four pretty noses in the direction of St Tropez to go and live the life for a few days. It was, after all, a once-in-a-life-time opportunity. But we had another goal. We were headed for Le Mans, to the greatest motor race in the world, armed not only with the four best usable supercars money can buy but also a series of questions that needed answers. Would the new GT class – a category instigated by the Automobile Club de L'Ouest for this year's race and one for which this magazine has long been campaigning to allow more recognizable road car-based racers to take part again – be a success, for instance?

Certainly the 911, Ferrari and Lotus, all three of which were due to be represented in tomorrow's race, were sending out the right sort of messages during the short blast from Calais to Paris. But would the GTs really look and sound exciting enough truly to thrill when running side by side with the fabulously noisy, disturbingly rapid Group C monsters from Peugeot and Toyota, or should they just stick to doing what they do best – being great road cars? Also, we were here to pick a winner from this quartet of expensive, exclusive and, above all, exotic machinery from the UK, Japan, Germany and Italy.

Ultimately, our goal was to establish who, out of Lotus, Honda, Porsche and Ferrari, makes the best real-world supercar in the business. And if the drive to Le Mans and back – which would involve climbing in and out of them more times than most owners would in half a year, covering 5,000 combined miles, burning 300 gallons of fuel and then taking them to Millbrook for a full workout – wasn't good enough to backdrop from which to draw a winner then it's doubtful whether any of us should be allowed to continue working in this business.

Crawling out of Paris in the thick of the densest French traffic jam any of us can ever recall, three things about our convoy were already becoming apparent. The First – how much more attention and affection the French public had in reserve for the Ferrari – was perhaps predictable, especially since the 348 had already blown the others into the water at Dover when it came to impressing the locals. Even so, the crowds that gathered like bees to honey wherever and whenever we parked it, and the comparative lack of enthusiasm for the other three, still came as something of a shock. Then again, the French have always had good taste.

The second early realization was just how much easier the Porsche and Honda were to live with in the infuriatingly bunged-up Peripheries traffic. In the Ferrari it was the weight of the clutch and the heavy unassisted steering – a nightmare below 5mph – that made us wish we'd come in a Toyota Corolla for an irrational hour or two. In the Lotus it was a combination of the appalling reflections in the screen and three-quarter windows, added to the fact that none of us could see more than a French front number plate out of the Esprit's letterbox of a rear window. That and the tantrum thrown by the highly sprung four-cylinder turbo engine – the idle speed when walkabout for half an hour – as the outside temperature soared.

The real shocker, only three hours into the journey, was that the Porsche was proving to be the car that everyone wanted to drive least. Its suspension had thumped its way down the auto route with about as much subtlety as a head-butt, the roar from its huge tyres had battered our ears into cabbage and yet somehow it felt soft, as if Porsche had altered the 911 Turbo's basic personality to make it less of a pure sports car and more of a GT.

The kickback through the steering was still there, but the feel, the non-stop conversation you had looked forward to whenever you'd stroked the wheel of a 911 previously, was no longer there. And the noise, that wonderful spine-chilling chainsaw-in-cotton-wool howl that every 911 has made since day one, appeared to have gone AWOL, too.

Sitting in the jam gave us time to ponder some other anomalies and annoyances. Like the Esprit's pathetic ventilation and ludicrously close pedals; the Ferrari's painfully awkward first-to-second gearshift (the lever is stupidly reluctant to disengage one gear or enter the next); the NSX's quite brilliant driving position with its all-electric seat adjustment, and the Porsche's superior visibility and general maneuverability in traffic.

Finally we get clear of Paris, out on to the auto route towards Le Mans. Over the next half an hour or so I chew on a few factual nuggets and begin to consider some history, of the race we are about to witness and the cars from which we are about to witness it.

The 911 is the oldest car here. And the newest; although the Porsche concept of slotting a flat six engine into the back of an inverted bath tub of a car is 30 years old this year, the gun-metal 3.6 Turbo you see here – the fastest production 911 yet – is absolutely brand new. And the changes compared with even last year's 911 Turbo are many.

For starters, this is the first time the 3.6-litre engine (already seen in the back of the Carrera 2 and 4) has been turbocharged; the old Turbo made do with the ancient 3.3-litre motor, which produced 320bhp compared with the 3.6's lip-smacking 360bhp. And naturally Porsche has beefed up the bits you'd expect to keep that extra power in check' the brakes are bigger and the spring/damper rates have been refettled.

Visually thee 3.6 Turbo rams home the message harder than any other 911 that it is serious about going places rapidly. The massive new 18ins alloys – 10ins wide at the back, 8 ins at the front and wearing 265/35 and 225/40 Yokohama's respectively – are hardly subtle in their approach but are about as effective as it gets when it comes to wheel warfare.

By contrast, the 348 looks almost dainty and certainly no different than it did when Ferrari announced at its 1990 launch that this was the car to replace the 328. But that's because it is the same, on the outside. Underneath Ferrari has executed a number of modifications, most of which were in response to criticism that the car was 'tricky' when pushed close to its limit, and too firm of ride. Hence the springs are now softer, the dampers are stiffer and the rear upper wishbones have been slightly reposititioned.

The quad-cam 3.4-litre V8 engine has gained a catalytic converter since we last encountered it, too, along with shorter gearing to counteract the small power drop – down from 300bhp to 295bhp. And the car now weighs a little less because one or two lighter components have been adopted, notably the new Japanese starter motor.

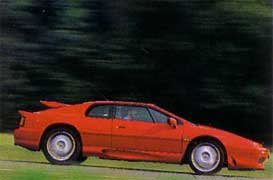

Mind you, that's nothing in comparison with the health farm from which the 18-year-old Esprit has just returned. The most significant area to have been toned is the steering, which gets power assistance for the first time and is all the better for it. But visually, too, Lotus's last surviving soldier, the S4, has been subject to the surgeon's knife; it gets more sober rear wing, new wheels, a modified bonnet, new front spoiler and side skirts and, at last, Vauxhall door handles in place of the dreadful Morris Marina cast-offs, while the cabin has been restyled. It's not a radical rethink, but the GM switchgear, beautifully sculpted steering wheel and relocated instruments, all housed in a Kevlar lookalike dashboard, are certainly a big improvement.

Even the four-cylinder turbo engine – on of the old car's strongest cards – wasn't left untouched, various changes having been made to enhance smoothness and refinement. Not that there's any more power. It still punches out a mighty 264bhp from just 2.2 litres, making it easily the most highly tuned of this group at 120bhp per litre.

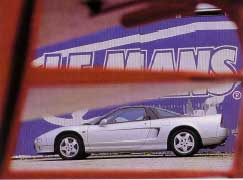

As for the NSX, it seems that Honda got it all right from the beginning. Not one change has been instigate since the car's debut in December 1990, although there are rumours that bigger wheels and tyres plus standard-fit power steering are on the way. If these are true, make sure you buy one now before the car is spoiled.

Now some race stuff. I've been to Le Mans seven times now, seven years on the trot. And I've loved it every year. There is, as they say, nothing like it. No other motor race has such atmosphere or is such a fantastic spectacle.

You can stand, or sit and eat at Les Hunaudiers restaurant, and watch the Group C space ships howl past at well over 200mph no more than 10 yards away on the Mulsanne straight. Then you can go to bed and get up to find they're still doing it, and will continue to do so for another six or seven hours. Blows me away every year.

But will it this year, I wonder, as we pay the toll on the outskirts of Le Mans and begin the slow bumble into town. The Peugeots will, I'm sure. And the Toyotas. But what about those GT cars – the XJ220s, 911s, Venturis, Esprits and the sole 348. Are they going to turn me on when they're being lapped every three or four laps by the big boys? Somehow I just can't see it.

And so it is. The race begins at 4pm on the Saturday and all I'm interested in, along with most of the other 200,000 fans who turn up to watch, is six works cars, the ones that threaten to pop my kidneys every time they scream by, sucked into the track and cornering at surreal speeds compared with the GT cars, thanks to their ground effects.

Would it be any different, I muse as the leading Peugeot takes the flag nine laps in front of two other Peugeots at 4pm on Sunday, if the field was full of Bugattis, McLarens and F40s instead of endless 911s, three rather boring looking and sounding XJ220s and a smattering of no-hopers? In other words, the sort of field that we and the Automobile Club de L'Ouest really wanted to see make up the grid. Almost certainly, but we'll just have to wait until next year to find out.

One thing is clear, though. The GT class is not for the cars we brought with us. They, as we secretly suspected all along, should stick to being road cars. Fabulous road cars.

Which is the most fabulous? We were about to find out. First we took them to the circuit, on the Monday when most but not all of the teams had packed up and gone home. Although it wasn't what we'd intended, a day to ourselves on the closed sections of the world's greatest race track wasn't something we were going to let slip.

Immediately the NSX feels at home on a track. So does the Ferrari. The others, notably the Porsche, feel like road cars out of their natural environment. Not like a fish out of water but like a good amateur golfer on the tee at the British Open.

It's the Honda's body control and its meaty yet beautifully positive steering that allows it to feel so natural through the Esses of Le Mans; both seem peerless. Until you try the Ferrari. In the 348 you've got the same degree of body control, the same iron tautness through the corners, but the steering – lighter than the Honda's but with much more feedback – lifts it clear of even the mighty NSX at La Sarthe.

The Esprit, though slower than the Porsche, is next best. It understeers less than the 911 and has much less turbo lag. But ultimately its nose will run wide of any given apex sooner than either the Ferrari's or Honda's. And it rolls more.

Oddly, the Porsche didn't feel right at Le Mans at all. Its front wheels were the first to let go by a surprisingly wide margin, its body, despite rockhard springs, was allowed to roll more through the faster corners, and in extreme conditions its tail would wag wider and more quickly than any of the others, including the Ferrari, which, it seems, has been tamed.

Unusually, that privileged track session – I had been aching to drive on it for years – would turn out to be a vital insight to our conclusion, but we still had 500 miles of hard on-road driving to savour before coming to any final decision. The results, believe me, were fascinating.

Let's deal with the 911 first. Every time anyone emerged from this car, having driven it rapidly in convoy with the others, they were almost expressionless. Which is astonishing for an £80,499 sports car with 360bhp that will, as we discovered later at Millbrook, sprint to 60mph in 4.6secs, to 100mph in a Viper-munching 10.6secs, record an incredible 3.9secs, between 80-100mph in fourth gear and go on to a maximum of 174mph, the second highest speed we have ever recorded around the Millbrook bank.

The 911 Turbo's problem is that despite its gorgeously gruesome looks, its fantastic brakes and its shattering acceleration (it is easily the quickest of the four here), a cooking Carrera 2 costing £30,000 less is more fun. More 911.

Over the B-roads we took back to Calais, the Porsche was fast – ver fast. But it was also hard work to steer accurately because of the constant kick-back through the wheel. And it simply wasn't as soul-stirring as the other three. For some reason it felt detached, almost arrogant.

The Lotus is the exact opposite. It always was a driver's car, the Esprit, but now that it has power steering the experience is that much more readily accessible. And no less potent. Although the bald performance figures we took later were fractionally down compared with the old SE, the S4 is still a very rapid car capable of hitting 60mph in 5.0secs flat and 100mph in 12.7secs and going to a maximum of 161mph. That makes it the second swiftest car here in terms of acceleration, if not top speed.

But the real reason we all preferred it to the Porsche on the final drive back, forgetting the fact that at £46,995 it cost £33,504 less to buy, is because it felt more of a sports car than the 911. From its steering right down to the exquisite feedback bursting out at you through its seat and chassis, the Lotus taught the Porsche lessons on supercar feel over every inch of those French B-roads. Which was both genuinely surprising but at the same time rather sad, from the point of view of a once hopeless 911 fan.

The only aspect that prevents it from going all the way is its quality. Although much improved, the Esprit struggles, in this company, to hide its roots. It doesn't feel cheap any more. But neither does it feel jet-set exclusive. The others do.

Especially the Ferrari. The 348 had already excelled itself on the circuit, but on the road it was better still. Too strong, even, for the NSX to contain.

The difference between these two cars is hard to quantify in tangible terms. Both are very similar performers (less accelerative than the Esprit and 911, although the Ferrari has a higher top speed than the Lotus at 163mph) and, up to a point, both behave similarly on the road. Initially only the 348's greater steering feel and harder ride sets them apart.

But the further we traveled and the hard we drove in France, the more special, the more unique the Ferrari felt. We argued long and hard over which of the two made the best noise under full throttle, although no one disputed the fact that the NSX was more refined overall and had vastly superior gearchange. But ultimately this is as much the Honda's problem as it is its strength. Because it is so well honed as an all-rounder, so easy to live with, it misses out on that last 10 per cent of pure, raw thoroughbred sports car appeal that makes the Ferrari such a deliciously rich experience.

Partly it is the steering; the NSX's is very good, the 348's exquisite. And partly it is the extra sharpness of the Ferrari's chassis, which is that crucial fraction more responsive to your inputs than not only the NSX but also any other supercar this side of £100,000 we can think of.

Also, when the day is through and you switch off, climb out and glance over your left shoulder on your way up to the front door, the Ferrari will stop you dead in your tracks and force you to stand and stare in awe of its almost sexual beauty. And it'll happen every time you park it. In the Honda you'll probably just smile, then put the key in the lock and close the door behind you. That's enough to justify the extra £17,000 on its own.

Factfile

Porsche 911 Turbo Ferrari 348tb Honda NSX Lotus Esprit S4 How fast? 0-60mph 4.6 secs 5.6 secs 5.8 secs 5.0 secs 0-100mph 10.6 secs 13.3 secs 13.7 secs 12.7 secs 50-70mph in 4th 4.9 secs 5.1 secs 6.3 secs 4.3 secs 80-100mph in 5th 5.9 secs 8.1 secs 9.8 secs 4.5 secs 30-70mph 3.7 secs 5.0 secs 4.9 secs 4.7 secs Top Speed 174mph 164mph 162mph 161mph Test mpg 14.1 17.9 20.7 16.0 Fuel range at test mpg 239 miles 375 miles 318 miles 256 miles How much? £80,499 £73,878 £56,950 £46,995 Engine Max power 360bhp/5500rpm 295bhp/7200rpm 270bhp/7100rpm 264bhp/6500rpm Max torque 383lb ft/4200rpm 238lb ft/4200rpm 210lb ft/5300rpm 261lb ft/3900rpm Specific output 98bhp/litre 88bhp/litre 90bhp/litre 121bhp/litre Power to weight 244bhp/tonne 205bhp/tonne 201bhp/tonne 197bhp/tonne Installation rear, longitudinal, rear-wheel drive mid, longitudinal, rear-wheel drive mid, transverse, rear-wheel drive mid, longitudinal, rear-wheel drive Capacity 3600cc, 6 cyls horizontally opposed 3405cc, 8 cyls in vee 2977cc, 6 cyls in vee 2174cc, 4 cyls in line Made of aluminium alloy head/block aluminium alloy head/block aluminium alloy head/block aluminium alloy head/block Bore/Stroke 100mm/76.4mm 85mm/75mm 90mm/78mm 95mm/76mm Compression ratio 7.5:1 10.4:1 10.2:1 8.0:1 Valves 2 per cyl, dohc 4 per cyl, dohc 4 per cyl, dohc 4 per cyl, dohc Ignition and fuel electronic ignition, K-Jetronic fuel injeciton electronic ignition, Bosch Motronic M25 fuel injection electronic ignition, Honda PGM-Fi fuel injection electronic ignition and fuel injection, chargecooled turbo Gearbox Type 5-speed manual 5-speed manual 5-speed manual 5-speed manual Ratios/mph per 1000rpm 1st 3.154/6.7 3.21/6.2 3.07/5.8 3.36/5.4 2nd 1.789/11.7 2.11/9.5 1.73/10.3 2.05/8.0 3rd 1.269/16.5 1.46/13.8 1.23/14.4 1.38/13.25 4th 0.967/21.7 1.09/18.5 0.98/18.3 1.03/17.75 5th 0.756/27.8 0.86/23.3 0.77/23.0 0.82/22.39 Final drive 3.44 3.44 4.06 3.89 Suspension Front wishbones, coil springs, dampers, anti-roll bar double wishbones, coil springs, dampers, anti-roll bar double wishbones, coil springs, dampers, anti-roll bar double wishbones, anti-roll bar Rear semi-trailing arms, coil springs, dampers, anti-roll bar double wishbones, dampers, anti-roll bar double wishbones, coil springs, dampers, anti-roll bar double wishbones, anti-roll bar Steering Type rack and pinion, power assisted rack and pinion rack and pinion rack and pinion, power assisted Lock to lock 2.8 turns 3.2 turns 3.4 turns 3.1 turns Brakes Front 322mm discs 299mm discs 282mm discs 259mm discs Rear 299mm discs 311mm discs 282mm discs 274mm solid discs Anti-lock standard standard standard standard Wheels & tyres Size front 8x18ins 7.5x17ins 6.5x15ins 7x17ins Size rear 10x18ins 9x17ins 8x16ins 8.5x17ins Made of alloy alloy alloy alloy Tyres front 225/40 ZR18 215/50 ZR17 205/50 ZR15 215/40 ZR17 Tyres rear 265/35 ZR18 255/45 ZR17 225/50 ZR16 245/45 ZR17 Made by Porsche AG, Stuttgart, Germany Ferrari SpA, Modena, Italy Honda Motor Co. Tokyo, Japan Lotus Engineering Ltd, Hethel, Norwich, UK

|

|